The Guardian recently polled ‘hundreds of the world’s top climate scientists’ (identified, apparently, on the basis of IPCC report authorship). A distressing 80 percent of them predicted at least 2.5C of global heating by the end of the twenty-first century. Only a handful felt the 1.5C target thought necessary for a chance at avoiding massive devastation and loss of life was still achievable.

Another point on which IPCC authors find themselves in striking consensus is on the political nature of this crisis. 3/4 apparently cited a ‘lack of political will’ and around 60 percent entrenched interests, notably the fossil fuel industry, as obstacles to responding to the crisis.

This is a consensus that, in effect, invites two different possible responses: One is to double down on efforts to summon the requisite ‘will’. Christina Figueres, the former head of the UNFCCC, responded to the Guardian survey with a call for ‘stubborn optimism’ in the face of climate despair: ‘We must take stock of the science, triple down on our efforts and deploy the perspective of possibility.’

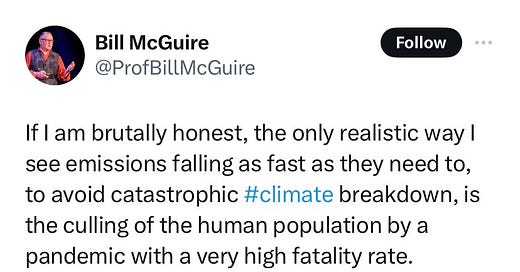

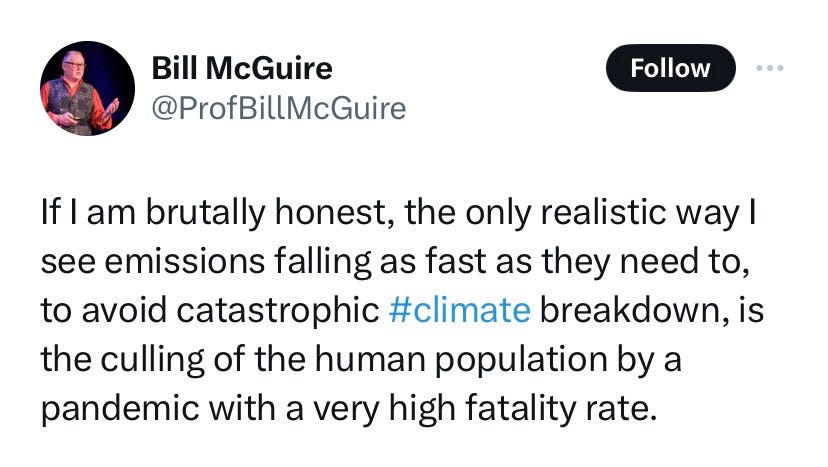

The other possibility is, in effect, to fantasize about some deus ex machina cutting through the political deadlock. As the former option of doubling (or, apparently ‘tripling’) down on efforts to find the necessary ‘will’ starts to appear increasingly Quixotic, we’re likely to see a lot more of the latter. The external forces invoked here range from murderous, eco-fascist fantasies about (another, more lethal) global pandemic as in… this (also from an IPCC author):

… to implausible fantasies about carbon capture, to more subtly murderous (if technically rather more plausible) proposals for things like solar radiation management (SRM), which cost relatively little and could be carried out unilaterally by any number of leading states or private actors.

The trouble with calls for will and climate ‘action’ is that there has, in fact, been a great deal of climate action over the last two decades. Governments across the globe, particularly in the global north, have put in place massive subsidy or tax credit schemes for the adoption of electric vehicles, solar arrays, building retrofits and the like. We’ve seen potentially massive programmes to mobilize private investment in green energy and other climate mitigation and adaptation activities, to offset carbon emissions. We’re in fact faced with a rather different problem: None of the actions thus far have worked. It is not a case of needing to summon greater will to push through ‘more’ climate action, but of needing qualitatively different measures than those we’ve had thus far. A focus on ‘more action’ thus promises little in and of itself.

Crossing fingers and hoping for divine intervention in the form of scaleable carbon capture is scarcely more likely to work out, though. Crossing fingers and hoping for the sudden untimely death of billions of people is no more likely to work out. But the fantasy itself flirts alarmingly closely with eugenicist population-focused responses to environmental degradation or climate apartheid in the form of the organized abandonment of the majority of the world. Both of which have plenty of precedent. Something like SRM is less overtly or directly murderous, but no less violent or authoritarian — it needs only a handful of powerful actors to implement, would have significant costs which would likely be borne unevenly. What matters is its ‘feasibility’ under the kind of assumptions common to mainstream climate politics. It’s worth taking seriously as the most likely manifestation of this response to ‘climate despair’.

The point I want to make here is that all of these responses, from fantasies about mega-murder to ‘stubborn optimism’ in search of ‘action’, are reflective of a crisis of liberal politics in the face of climate crisis. The majority of IPCC authors are correct, after a fashion, in diagnosing the political roots of the crisis: our institutions of governance as they exist cannot meaningfully address the crisis they’re faced with. These disparate responses to that impasse have in common the implicit assumption that we cannot be governed otherwise. The liberal-capitalist state and its international appendages are the limit of thinkable politics. So we’re left with the choice between ‘stubbornly’ running up against their limitations or seeking extra-political intervention. Authoritarian, even fascist responses to climate crisis are dangerous precisely because they’re only a couple steps away from the liberal mainstream of our climate politics.

***

It’s helpful here to reach for Gramsci. Specifically, it’s useful to understand the present as a situation of ‘organic crisis’ — summed up through the over-quoted aphorism that ‘the old is dying and the new cannot yet be born’. Situations of organic crisis are those in which the reproduction of the current order is impossible, and the state such as it exists lacks adequate means to secure that reproduction (the old is dying), but no force yet exists that can force through a revolutionary overhaul of state and social order (the new cannot be born).

This is a useful way to grasp the impasse in global climate politics. The climate crisis represents a threat, ultimately not only to the survival of many of us but to the reproduction of capitalism. Take, for instance, the litany of studies estimating that significant climate damage to global GDP has already taken place, and predicting worse to come. (For all the caveats we ought to acknowledge about ‘GDP’ as a measure of anything.) If capitalist social relations, in James O’Connor’s words, tend generally to ‘self-destruct by impairing or destroying rather than reproducing their own conditions’, the climate crisis represents a crisis of the reproduction of capitalist social relations on a global scale. For a litany of reasons, some structural and some conjunctural, capitalist states as they exist are unable to remedy this crisis. They are structurally bound to promote the accumulation of capital in the concrete forms manifested within their territory (which, for quite a few states means the extraction and combustion of fossil fuels), and have been systematically stripped of bureaucratic and fiscal capacity by several decades of conjoined neoliberal restructuring of governance and the accompanying global restructuring of production. The constant resort to ‘mobilizing private finance’, I’ve argued, really is the best that capitalist states can do at the moment. So, the old is dying.

But, neither crises of accumulation nor the social and ecological crises provoked by the intensification of capitalist contradictions, for Gramsci, are sufficient in and of themselves to call into being a new social order. Historic change, Gramsci notes, ‘can come about… because hardship has become intolerable and no force is visible in the old society capable of mitigating it’. But crucially this depends on a configuration of the wider ‘relations of force’ capable of installing that new order: ‘A crisis cannot give the attacking forces the ability to organise with lightning speed in time and in space; still less can it endow them with fighting spirit’. What we need is not ‘stubborn optimism’, but nothing less than a configuration of social forces capable of forcing a foundational restructuring of state and property relations as they exist. It would be a separate essay altogether to argue about the prospects for such a ‘historic bloc’ and how it might be brought about, for present purposes it’s probably uncontroversial to say that this does not yet exist.

So we find ourselves stuck with so many ‘morbid symptoms’. Gramsci suggests that

If this process of development from one moment to the next is missing… the situation is not taken advantage of, and contradictory outcomes are possible: either the old society resists and ensures itself a breathing space, by physically exterminating the élite of the rival class and terrorising its mass reserves; or a reciprocal destruction of the conflicting forces occurs, and peace of the graveyard is established.

We approach, or indeed for the global majority we passed some time ago, the point where the hardships imposed by contemporary capital accumulation have become ‘intolerable’. And there is indeed as of yet no force in the current political-economic order capable of mitigating it. Capitalist state forms are increasingly inadequate, but there remains no social force or combination of social forces yet capable of inaugurating an alternative. We are thus living through so many efforts to secure some form of ‘breathing room’ (I appreciate the irony of the term ‘breathing room’ here…)

One common way through these crises, Gramsci suggests, is through ‘Caesarism’. Caesarism, in Gramsci’s usage, refers to an ‘external’ intervention, cutting through such stalemated political conjunctures ‘it may happen that neither A nor B defeats the other – that they bleed each other mutually and then a third force C intervenes from outside, subjugating what is left of both A and B’. Though Caesarism is often equated here with authoritarian and personalistic forms of rule (most notably with Mussolini’s fascism), ‘Caesarist solution can exist even without a Caesar, without any great, “heroic” and representative personality’. Importantly, the ‘external’ character of Caesarist forces does not imply their neutrality — Gramsci distinguishes between ‘reactionary’ Caesarisms leading to the restoration of the old social order and historically progressive ones.

***

So what does this have to do with SRM, or with praying for a plague? It’s notable that, around SRM in particular, proponents are often explicit about the need to cut through the political deadlock around the climate crisis. SRM entails injecting reflective particles (most often sulphur dioxide) into the upper atmosphere. It promises to cool the planet not by reducing greenhouse gas emissions, but by reducing the amount of incoming energy that can be trapped by them.

The unintended consequences of SRM are potentially pretty severe. Scientists debate the potential impact on agriculture (plants need sunlight to grow, but the heat and extreme weather SRM aims to mitigate are also bad for crops), sulphur dioxide itself is harmful to people and planet (it’s the main driver of acid rain, and a main component of smog). And the consequences for weather systems, rainfall, and the like are unpredictable. SRM is, at best, hugely risky.

Even advocates will happily grant this. The calculus is explicitly not so much whether SRM is safe as whether it would likely kill more or less people than 2.5C or 3C of warming. In the words of David Keith, a physicist writing in the New York Times, ‘Air pollution deaths from the added sulfur in the air would be more than offset by declines in the number of deaths from extreme heat, which would be 10 to 100 times larger’. US policymakers have also been explicit that this is the framework within which the risks of SRM need to be considered: ‘The potential risks and benefits to human health and well-being associated with scenarios involving the use of SRM need to be considered relative to the risks and benefits associated with plausible trajectories of ongoing climate change not involving SRM’.

SRM might be risky, even deadly. It is also, however, very importantly, ‘cheap’, and likely possible for leading states and even some private actors to implement unilaterally. Estimates from Harvard’s Solar Geoengineering Research Programme peg the cost of a programme of stratospheric aerosol injection at a ‘remarkably inexpensive’ $2-2.5 billion per year. Governments need not necessarily be involved at all — US-based startup Making Sunsets caused significant controversy last year with a series of unauthorized experiments releasing sulphur dioxide into the atmosphere from Mexico.

In short, what SRM offers most of all, within the context of an impoverished liberal political imaginary, is thus the possibility of a climate solution allowing an end-run around politics. As one typical formulation puts it, ‘with political gridlock and our inability to accelerate collective climate action, we need a backup plan’. In the words of one US think-tanker with ties to the Biden administration, quoted by Politico, ‘Politicization around climate change has obviously been the huge driver” of policy gridlock on reducing carbon emissions… “And so I think trying to avoid politicization around geoengineering is also important”.’ The possibility of unilateral action on the climate through SRM is undoubtedly part of its appeal to many: ‘In an ideal world, the United States would not begin geoengineering without an international agreement and a global system of governance to supervise the effort. But our world is not ideal, and it is unimaginable that global consensus on geoengineering could be reached any time soon.’

The hope, in short, is for the unilateral implementation of SRM to act as a ‘force that intervenes from the outside’. For a powerful state, or even just a committed rich person, to cut through the political impasse and impose a restoration of the old social order. This is a reactionary Caesarist politics. The political logic behind advocacy of SRM is certainly contested. SRM itself is controversial, subject to numerous efforts at moratoria on implementing and even on experiments until its possible effects are better understood. Claims that SRM, which is currently being developed and promoted almost entirely within the metropolitan core, would in fact benefit the global poor most of all have been intensely contested. There is nothing like an elite consensus around SRM at the minute. But SRM is very much in keeping with the current direction of climate politics. It is very much a product of an understanding of the politics of climate change which runs between ‘stubborn optimism’ and despair, and lives and dies by ‘action’ and the capacity for ‘political will’. This is a political crisis that has the mainstream of the climate debate already casting about for Caesars.

***

The point of all this is that the impasse of climate politics is very much real, but not one that can be resolved with optimism or will, nor by evading politics altogether. Or, in the latter case, at least not without considerable violence. It is, in Gramsci’s terms, a situation of organic crisis. Our existing institutions really cannot meaningfully respond to this crisis. If I’m not exactly offering much here in the way of advice on how we might ‘organize the attacking forces’ in a way that might allow us to move beyond them, I hope I’m at least underlining why we need to fight the impoverished imaginaries of existing political debate, increasingly reduced to seeking some Caesar to come in and resolve things.